Little Liberia Image Gallery

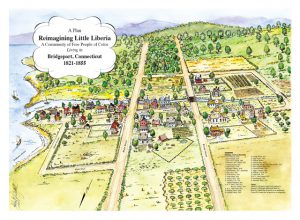

Indeed, the story of how a group of Black and Native Americans from throughout southwestern Connecticut, Virginia, Maryland, New York, and the West Indies transformed an isolated and undesirable part of town into a thriving “peri-urban multi-ethnic enclave,” in the early nineteenth century; is generally not known …The lack of historical data on Bridgeport’s free nineteenth century community of color in conventional city and regional archives has rendered their legacies of freedom, entrepreneurship, and cultural innovation invisible…

In retelling the story of Little Liberia, scholars and public historians have been aware that it is not just about telling the story of what happened in one place at one time, but rather it is about telling the many stories that shaped this site, and how the site was connected to many other places throughout the Atlantic world by land, sea, and concepts of freedom. From nearby Derby, CT to New Bedford, MA, Little Liberians like Mary and Eliza Freeman were deeply connected to a wider Black Atlantic community that was boldly and bravely seeking to create new opportunities for Black and Native American citizenship, outside of the denigrating contexts of slavery and servitude.

Dr. Jamila Moore Pewu, PhD, California State University, Fullerton, 2015

HISTORY

On April 10, 1821, Seth B. Jones, a white man, conveyed a house in what is now Bridgeport, CT’s South End to two men of color, John Feeley (1781-1862) and Jacob Freeman (died August 22, 1832). And seeds for the growth of Bridgeport’s historic “Liberia” were sown. According to the deed, each secured “an undivided half interest in land and dwelling house and other buildings in Bridgeport.” This land may have been considered undesirable to whites, perhaps because it was close to salt marshlands and the threat of malaria. Settlement began in earnest when Joel Freeman (circa 1791-1865) arrived in 1828 from Derby, CT. A leader of Black and Paugussett heritage, Joel worked on a West India schooner. He became Liberia’s patron and lynchpin.

Liberia means “Free Land.” For people of color to call their prosperous settlement Liberia in in the 1840’s was bold indeed, if not defiant. Connecticut didn’t end slavery until 1848; the nation ended it in 1865. At a time when 90% of all African Americans were in shackles, considered chattel, the residents of this self-engendered community approached landowners, engaged builders, and planned every phase of its development. Liberia was referred to as Ethiope in deeds prior to the early 1940’s. In the 20th century the community was fondly referred to as “Little Liberia” differentiating it from the African nation.

Little Liberia was a stubborn victim of early urban redevelopment; the construction of public park land (much like Manhattan’s Seneca Village); and segregation in housing, jobs, and education imposed by State law. These were some of the powerful forces responsible for the dissipation of Bridgeport’s Liberia after the Civil War.

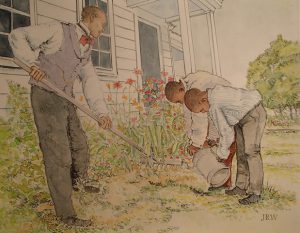

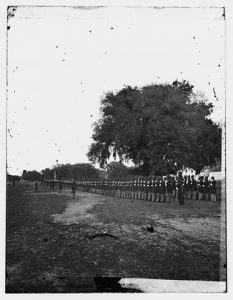

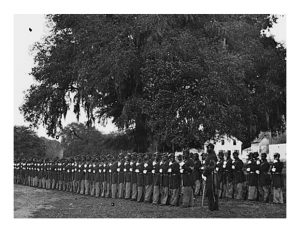

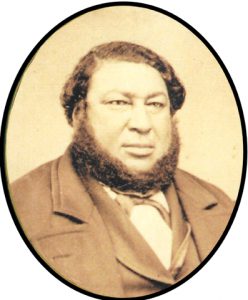

ABOUT THE GALLERY

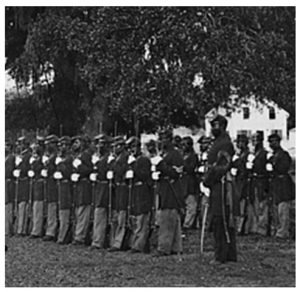

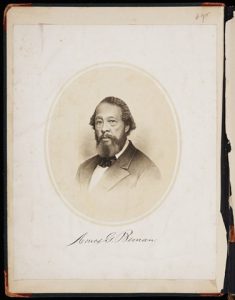

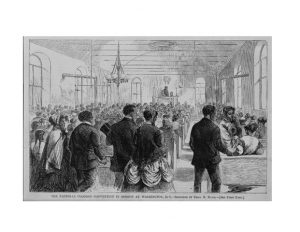

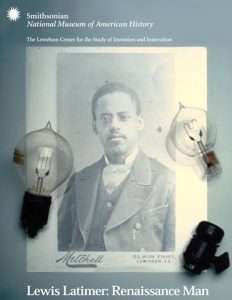

There are few known photos of Little Liberia’s African & Native American residents, so this gallery also features some of their contemporaries. Men of Little Liberia co-authored calls for abolition, emancipation, enfranchisement, social and economic justice with Rev. Amos G. Beman as part of the sweeping Colored Convention Movement. Frederick Douglass published a letter about Little Liberia in his newspaper. Residents fought and died in the Civil War. Following in the footsteps of the grandfather of two settlement founders, Nero Hawley, who served with George Washington at Valley Forge. Paugussett patriarch William Sherman, who provided the Trumbull land (Reservation) for his descendants, was a resident. As was inventor Lewis Latimer who worked for Thomas Edison and engineered the breakthrough that made the light bulb commercially viable and available to us today. Scenes of daily life are depicted, including school with John Baker who moved here from Brooklyn’s Weeksville.